A Blog about [1] Corporate Governance issues in Malaysia and [2] Global Investment Ideas

Friday, 31 August 2012

The Investor Sentiment Wheel

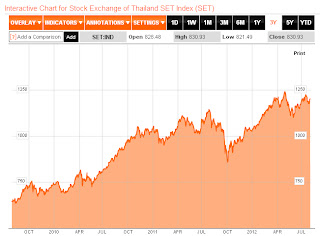

In the 1993 bull run the youngest office boys gave out stock tips, a classic telltale sign that share prices were very rich. Malaysia looked to be on a roll, but structural problems were ignored. In 1994 prices softened somewhat, but the real reckoning came in 1997/98, when it turned out that the economy was not that good, after all. It looked like the world was coming to an end (at least for Malaysia) and the KLCI index reached a low of 250. For those who had cash and a lot of guts there was an excellent buying opportunity. Prices recovered in the next decade, with moderate crashes during the Dotcom bubble and SARS. In 2007 it looked like the global economy was going very well, but again structural problems were overlooked and in 2008/9 the house came down. Not so much in Malaysia (my guess is through artificial support by government linked funds), but there were tremendous buying opportunities in other Asian countries, for instance in Hong Kong.

With hindsight, everything is easy. The difficulty lies in having the right mentality, to invest when all the news is bad, and to sell when all the news appears to be good. A decent way to deal with this problem is dollar cost averaging, invest the same amount of money each month.

Thursday, 30 August 2012

Kai-Fu Lee Rips into “Ignorance and Deception” of Short Sellers Citron (updated)

Update: the parties continue to fight, a new article at TechInAsia can be found here.

I like websites that expose corporate misdeeds, but there is one group of websites that are rather suspect, for the simple reason that they make money from this. These are the websites linked to short sellers. First they analyse a potential short selling candidate (in this case often Nasdaq listed Chinese companies), if they do find wrong doings they will first take a "short" position and only then expose their findings.

Selling "short" means they sell shares that they don't have, if the share does indeed go down they then buy back the shares at a cheaper price, closing the short position and their profitable trade.

Citron Research is one of those companies, they did have some success in the past, but they might have made some mistakes in recent cases. TechInAsia, a Singapore based website reporting about regional tech stories, reports:

"One of China’s top tech luminaries, Kai-Fu Lee, has ripped into the short sellers Citron Research – branding their methodology “despicable” – after Citron released a new report about the Chinese web portal Sohu (NASDAQ:SOHU) and its Sogou search engine. Mr Lee, the former president of Google China and now the CEO of incubator Innovation Works, condemns the repeated short-selling of US-listed China stocks as “already questionable” before then pointing out the many factual errors – the “ignorance and deception;” the “holes and lies” – in the latest Citron post.

Kai-Fu Lee, in his first post on XueQiu, singles out “how these short sellers take advantage of the information asymmetry between China and the US,” making false likenesses and providing other bits of vague information that it can be tough for US investors to research and verify. His post is written in English, not Chinese, and is presumably aimed at such overseas investors."

I recommend readers to read the whole article on TechInAsia, and the original by Ka--Fu Lee which can be found here.

Unfortunately, this does not mean that Chinese companies listed on the Nasdaq suddenly do not have any (accounting or other) issues. But it does mean that not any report can be trusted at face value and readers have to do their own research.

Buyer beware, as usual.

I like websites that expose corporate misdeeds, but there is one group of websites that are rather suspect, for the simple reason that they make money from this. These are the websites linked to short sellers. First they analyse a potential short selling candidate (in this case often Nasdaq listed Chinese companies), if they do find wrong doings they will first take a "short" position and only then expose their findings.

Selling "short" means they sell shares that they don't have, if the share does indeed go down they then buy back the shares at a cheaper price, closing the short position and their profitable trade.

Citron Research is one of those companies, they did have some success in the past, but they might have made some mistakes in recent cases. TechInAsia, a Singapore based website reporting about regional tech stories, reports:

"One of China’s top tech luminaries, Kai-Fu Lee, has ripped into the short sellers Citron Research – branding their methodology “despicable” – after Citron released a new report about the Chinese web portal Sohu (NASDAQ:SOHU) and its Sogou search engine. Mr Lee, the former president of Google China and now the CEO of incubator Innovation Works, condemns the repeated short-selling of US-listed China stocks as “already questionable” before then pointing out the many factual errors – the “ignorance and deception;” the “holes and lies” – in the latest Citron post.

Kai-Fu Lee, in his first post on XueQiu, singles out “how these short sellers take advantage of the information asymmetry between China and the US,” making false likenesses and providing other bits of vague information that it can be tough for US investors to research and verify. His post is written in English, not Chinese, and is presumably aimed at such overseas investors."

I recommend readers to read the whole article on TechInAsia, and the original by Ka--Fu Lee which can be found here.

Unfortunately, this does not mean that Chinese companies listed on the Nasdaq suddenly do not have any (accounting or other) issues. But it does mean that not any report can be trusted at face value and readers have to do their own research.

Buyer beware, as usual.

Sunday, 26 August 2012

Astro playing the listed/delisted/relisted game

Astro Malaysia Holdings Bhd (Astro) has announced it will list again on the Bursa Malaysia, the latter will most likely appreciate to have another heavyweight on share market.

But again, as many other listings lately (Bumi Armada, IHH, Malakof), this is (partially) a repackaged company that has been listed before. It all seems rather puzzling, what is the rationale about this all? Who are the winners in these exercises, and, more importantly, who are the losers?

The authorities are so confident about improved corporate governance standards in Malaysia, so surely prospective investors will be well informed about this all. But are they really?

The "Exposure draft" prospectus can be found here at the website of the Securities Commission. The size of it is enormous, 10.8Mb, 596 pages. Is there actually an investor who will read this all?

But quantity is no substitute for quality, so we really would like to see all the relevant information in the prospectus.

If we search for the word "delist" we only receive some explanation on page 52:

A few more hits don't add any information at all to this. But this information seems to sidestep the most important issues at hand, like:

Why are these important questions not answered, why is there only one small paragraph about its previous listed history, while the whole prospectus contains almost 600 pages.

Ze Moolah also blogged about Astro, and he quotes a stunning revelation that the company was delisted at RM 8.3 Billion, will be listed again around RM 18.7 Billion just two years later, for a cool RM 10 Billion difference, or RM 10,000,000,000.00. And even more stunning, the company is relisting without its overseas operations.

Surely Astro should detail these issues in its prospectus. Why is the current valuation reasonable, when the larger company was delisted at a much lower valuation, which was deemed to be "fair and reasonable"? The independent advice circular can be found here.

Salvatore Dali also blogged about Astro. He expects the IPO to be well received, which is quite possible, since government linked funds will most like "support" the share price.

Another interesting remark from Salvatore Dali: "Plus retail players can again raise their hands in the air and say the same thing, good ones you bypass us, tough ones you come to us."

How true, when large IPO's are made, retail investors have to do with peanut allocations, sometimes as small as 2% of the amount of shares. Smaller IPO's however, which are not supported by government linked funds, have large allocations for the public. But so many times these companies have disappointed, from the very first day they are listed. And the authorities have hardly ever taken any action against the promoters.

It all seems very artificial to me, and does not have much to do with a free market, but the authorities seems to be very satisfied with all of this. If retail investors actually like what they see and have confidence in what is going on, is something else. Another issue is the puzzling lack of information about previous delisting exercises.

But again, as many other listings lately (Bumi Armada, IHH, Malakof), this is (partially) a repackaged company that has been listed before. It all seems rather puzzling, what is the rationale about this all? Who are the winners in these exercises, and, more importantly, who are the losers?

The authorities are so confident about improved corporate governance standards in Malaysia, so surely prospective investors will be well informed about this all. But are they really?

The "Exposure draft" prospectus can be found here at the website of the Securities Commission. The size of it is enormous, 10.8Mb, 596 pages. Is there actually an investor who will read this all?

But quantity is no substitute for quality, so we really would like to see all the relevant information in the prospectus.

If we search for the word "delist" we only receive some explanation on page 52:

A few more hits don't add any information at all to this. But this information seems to sidestep the most important issues at hand, like:

- At what share price and market cap was Astro before listed in 2003?

- At what share price and market cap was Astro delisted in 2010?

- How many shares were compulsory acquired?

- How does the market cap, turnover, earnings of the current Astro compare to those of the delisted company?

- Why was Astro listed before, why did it change its mind and delisted again?

- Why is Astro listing again, such a short while after it delisted?

- And why would Astro not delist again, having done so before?

Why are these important questions not answered, why is there only one small paragraph about its previous listed history, while the whole prospectus contains almost 600 pages.

Ze Moolah also blogged about Astro, and he quotes a stunning revelation that the company was delisted at RM 8.3 Billion, will be listed again around RM 18.7 Billion just two years later, for a cool RM 10 Billion difference, or RM 10,000,000,000.00. And even more stunning, the company is relisting without its overseas operations.

Surely Astro should detail these issues in its prospectus. Why is the current valuation reasonable, when the larger company was delisted at a much lower valuation, which was deemed to be "fair and reasonable"? The independent advice circular can be found here.

Salvatore Dali also blogged about Astro. He expects the IPO to be well received, which is quite possible, since government linked funds will most like "support" the share price.

Another interesting remark from Salvatore Dali: "Plus retail players can again raise their hands in the air and say the same thing, good ones you bypass us, tough ones you come to us."

How true, when large IPO's are made, retail investors have to do with peanut allocations, sometimes as small as 2% of the amount of shares. Smaller IPO's however, which are not supported by government linked funds, have large allocations for the public. But so many times these companies have disappointed, from the very first day they are listed. And the authorities have hardly ever taken any action against the promoters.

It all seems very artificial to me, and does not have much to do with a free market, but the authorities seems to be very satisfied with all of this. If retail investors actually like what they see and have confidence in what is going on, is something else. Another issue is the puzzling lack of information about previous delisting exercises.

Tuesday, 21 August 2012

Sad But True: Corporate Crime Does Pay

Almost daily we read about another apparently stiff financial penalty meted out for corporate malfeasance. This year corporations are on track to pay as much as $8 billion to resolve charges of defrauding the government, a record sum, according to the Department of Justice. Last year big business paid the SEC $2.8 billion to settle disputes.

Sounds like an awful lot of money. And it is, for you and me. But is it a lot of money for corporate lawbreakers? The best way to determine that is to see whether the penalties have deterred them from further wrongdoing.

The empirical evidence argues they don’t. A 2011 New York Times analysis [3] of enforcement actions during the last 15 years found at least 51 cases in which 19 Wall Street firms had broken antifraud laws they had agreed never to breach. Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America, among others, have settled fraud cases by stipulating they would never again violate an antifraud law, only to do so again and again and again. Bank of America’s securities unit has agreed four times since 2005 not to violate a major antifraud statute, and another four times not to violate a separate law. Merrill Lynch, which Bank of America acquired in 2008, has separately agreed not to violate the same two statutes seven times since 1999.

Outside the financial sector the story is similar. Erika Kelton at Forbes reports [4] that Pfizer paid $152 million in 2008; $49 million a few months later; a record-setting $2.3 billion in 2009 [5] and $14.5 million last year. Each time it legally promised to adhere to federal law in the future. Each time it broke that promise.

The SEC could bring contempt of court charges against serial offenders, but it doesn’t. Earlier this year the SEC revealed it has not brought any contempt charges against large financial firms in the last 10 years. Adding insult to insult the SEC doesn’t even publicly refer to previous cases when filing new charges.

We know that CEOs of big corporations never go to jail. We probably didn’t know they often benefit financially even when the corporations under their control violate the law. GlaxoSmithKline CEO Andrew Witty recently received a significant pay boost to roughly $16.5 million just four months after Glaxo announced it will pay $3 billion to settle federal allegations of illegal marketing of many of its prescription drugs. Johnson & Johnson Chairman and CEO William Weldon received a 55 percent increase in his annual performance bonus for 2011 and a pay raise despite a settlement J&J is negotiating with the Justice Department that could run as high as $1.8 billion.

What level of penalty might deter corporate crime? The Economist magazine recently addressed [6] that question. It used the common sense framework proposed by University of Chicago economist Gary Becker in an influential 1968 essay. Becker proposed that criminals weigh the expected costs and benefits of breaking the law. The expected cost of lawless behavior is the product of two things: the chance of being caught and the severity of the punishment if caught.

Purdue Economics Professors John M. Connor and C. Gustav Helmers examined [7] the market impact of over 280 private international cartels from 1990 to 2005 and the fines imposed on them by various governments. They estimated these criminal conspiracies in restraint of trade raised prices by $260-550 billion. The median overcharge was about 25 percent of affected commerce.

Thus a fine about 25 percent of revenue would repay the damage done. But that’s assuming wrongdoing is caught every time. The Economist suggests that catching one in three violations would constitute a good track record for regulators. That would mean a fine of 75 percent of revenue would be needed to deter future violations. But the study found that actual fines ranged only between 1.4 percent and 4.9 percent.

Last year’s SEC settlement regarding Citigroup’s fraudulent mortgage investment practices fits that pattern. The settlement was for $285 million, less than 4 percent of Citigroup’s $76 billion in revenues.

Often federal penalties are so low they might be viewed as an invitation to break the law. According to the Times, Citigroup had cheated investors out of more than $700 million, more than twice what it paid in penalties.

As for Glaxo’s $3 billion settlement, George Lundberg, for 17-years Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of the American Medical Association writes [8], “The penalty sounds like a lot of money but that company made probably 10 times that much from its illegal actions.”

What can be done? A first step might be for the media to stop reporting simply the gross settlement figure and instead give us the information that allows us to decide whether the punishment fits the crime. A few days ago a brief story in the New York Times business section admirably achieved this goal.

The Times reported [9] that in 2006 Morgan Stanley entered into a complex swap agreement with the New York electricity provider KeySpan that gave it a stake in the profits of a competitor. This enabled the two companies to push up the price of electricity. Morgan Stanley broke the law. On August 7 a federal judge approved the settlement between the Justice Department and Morgan Stanley.

Here’s the cost benefit analysis. The total cost to New Yorkers in higher utility bills because of the price fixing came to $300 million. Morgan Stanley was paid $21.6 million for handling the swap agreement. And the financial penalty imposed on Morgan Stanley? An inconceivably low $4.8 million. In addition the bank didn’t have to admit any wrongdoing. There will be no further prosecution.

Anyone who read this story had all the facts necessary to conclude that something is terribly, even criminally wrong here. The Times is to be commended for going that extra step and providing a full cost-benefit analysis. I hope it can become a template for all political and business reporters.

Article from David Morris on Alternet. How would this story compare to Malaysia?

Sounds like an awful lot of money. And it is, for you and me. But is it a lot of money for corporate lawbreakers? The best way to determine that is to see whether the penalties have deterred them from further wrongdoing.

The empirical evidence argues they don’t. A 2011 New York Times analysis [3] of enforcement actions during the last 15 years found at least 51 cases in which 19 Wall Street firms had broken antifraud laws they had agreed never to breach. Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America, among others, have settled fraud cases by stipulating they would never again violate an antifraud law, only to do so again and again and again. Bank of America’s securities unit has agreed four times since 2005 not to violate a major antifraud statute, and another four times not to violate a separate law. Merrill Lynch, which Bank of America acquired in 2008, has separately agreed not to violate the same two statutes seven times since 1999.

Outside the financial sector the story is similar. Erika Kelton at Forbes reports [4] that Pfizer paid $152 million in 2008; $49 million a few months later; a record-setting $2.3 billion in 2009 [5] and $14.5 million last year. Each time it legally promised to adhere to federal law in the future. Each time it broke that promise.

The SEC could bring contempt of court charges against serial offenders, but it doesn’t. Earlier this year the SEC revealed it has not brought any contempt charges against large financial firms in the last 10 years. Adding insult to insult the SEC doesn’t even publicly refer to previous cases when filing new charges.

We know that CEOs of big corporations never go to jail. We probably didn’t know they often benefit financially even when the corporations under their control violate the law. GlaxoSmithKline CEO Andrew Witty recently received a significant pay boost to roughly $16.5 million just four months after Glaxo announced it will pay $3 billion to settle federal allegations of illegal marketing of many of its prescription drugs. Johnson & Johnson Chairman and CEO William Weldon received a 55 percent increase in his annual performance bonus for 2011 and a pay raise despite a settlement J&J is negotiating with the Justice Department that could run as high as $1.8 billion.

What level of penalty might deter corporate crime? The Economist magazine recently addressed [6] that question. It used the common sense framework proposed by University of Chicago economist Gary Becker in an influential 1968 essay. Becker proposed that criminals weigh the expected costs and benefits of breaking the law. The expected cost of lawless behavior is the product of two things: the chance of being caught and the severity of the punishment if caught.

Purdue Economics Professors John M. Connor and C. Gustav Helmers examined [7] the market impact of over 280 private international cartels from 1990 to 2005 and the fines imposed on them by various governments. They estimated these criminal conspiracies in restraint of trade raised prices by $260-550 billion. The median overcharge was about 25 percent of affected commerce.

Thus a fine about 25 percent of revenue would repay the damage done. But that’s assuming wrongdoing is caught every time. The Economist suggests that catching one in three violations would constitute a good track record for regulators. That would mean a fine of 75 percent of revenue would be needed to deter future violations. But the study found that actual fines ranged only between 1.4 percent and 4.9 percent.

Last year’s SEC settlement regarding Citigroup’s fraudulent mortgage investment practices fits that pattern. The settlement was for $285 million, less than 4 percent of Citigroup’s $76 billion in revenues.

Often federal penalties are so low they might be viewed as an invitation to break the law. According to the Times, Citigroup had cheated investors out of more than $700 million, more than twice what it paid in penalties.

As for Glaxo’s $3 billion settlement, George Lundberg, for 17-years Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of the American Medical Association writes [8], “The penalty sounds like a lot of money but that company made probably 10 times that much from its illegal actions.”

What can be done? A first step might be for the media to stop reporting simply the gross settlement figure and instead give us the information that allows us to decide whether the punishment fits the crime. A few days ago a brief story in the New York Times business section admirably achieved this goal.

The Times reported [9] that in 2006 Morgan Stanley entered into a complex swap agreement with the New York electricity provider KeySpan that gave it a stake in the profits of a competitor. This enabled the two companies to push up the price of electricity. Morgan Stanley broke the law. On August 7 a federal judge approved the settlement between the Justice Department and Morgan Stanley.

Here’s the cost benefit analysis. The total cost to New Yorkers in higher utility bills because of the price fixing came to $300 million. Morgan Stanley was paid $21.6 million for handling the swap agreement. And the financial penalty imposed on Morgan Stanley? An inconceivably low $4.8 million. In addition the bank didn’t have to admit any wrongdoing. There will be no further prosecution.

Anyone who read this story had all the facts necessary to conclude that something is terribly, even criminally wrong here. The Times is to be commended for going that extra step and providing a full cost-benefit analysis. I hope it can become a template for all political and business reporters.

Article from David Morris on Alternet. How would this story compare to Malaysia?

Scary chart

Everybody will still remember the devastation of the global economic recession of 2008/2009. Guess what, the 30-year US treasury yield is currently back to the level it reached in the midst of the crisis. Pretty remarkable since there is no large global recession at the moment, although lots of gloomy indicators all over the world and some countries indeed in negative territory. Malaysia seems to have escaped the gloomy mood, most likely caused by the recent economic stimulus.

Monday, 20 August 2012

Where has the US retail investor gone?

Excellent article from Barry Ritholtz in The Washington Post and highly relevant for the Malaysian situation. The message is clear, don't follow the US example, all the new inventions in financial engineering (derivatives, high frequency trading, etc) have not done anything good. In the contrary, confidence of retail investors is at a low, and they have gone home. Many people in the US believe the game is rigged against them, surely this also holds in Malaysia.

Lots of folks are wondering what happened to the Main Street-mom-and-pop retail investors. They seem to have taken their ball and gone home. I don’t blame them for feeling put upon, but it might be instructive to figure out why. Perhaps it could even help us determine what this means for risk capital.

We see evidence of this all over the place: The incredibly light volume of stock trading; the abysmal television ratings of CNBC; the closing of investing magazines such as Smart Money, whose final print issue is on newsstands as it transitions to a digital format; the dearth of stock chatter at cocktail parties. Why, it is almost as if America has fallen out of love with equities.

Given the events of the past decade and a half, this should come as no surprise. Average investors have seen not one but two equity collapses (2000 and 2008). They got caught in the real estate boom and bust. Accredited investors (i.e., the wealthier ones) also discovered that venture capital and private equity were no sure thing either. The Facebook IPO may have been the last straw.

What has driven the typical investor away from equities?

The short answer is that there is no single answer. It is complex, not reducible to single variable analysis. This annoys pundits who thrive on dumbing down complex and nuanced issues to easily digestible sound bites. Television is not particularly good at subtlety, hence the overwhelming tendency for shout-fests and silly bull/bear debates.

The factors that have been weighing on people-formerly-known-as-stock-investors are many. Consider the top 10 reasons investors are unenthused about the stock market:

1 Secular cycle: As we have discussed before, there are long-term cycles of alternating bull and bear markets. The current bear market that began in March 2000 has provided lots of ups and downs — but no lasting gains. Markets are effectively unchanged since 1999 (the Nasdaq is off only 40 percent from its 2000 peak).

The way secular bear markets end is with investors ignoring stocks, enormous P/E multiple compression and bargains galore. Bond king Bill Gross and his Death of the Cult of Equities is a good sign we are getting closer to the final denouement.

2 Psychology: Investors are scarred and scared. They have been scarred by the 57 percent crash in the major indexes from the 2007 peak to the 2009 bottom. They are scared to get back into equities because that is their most recent experience, and it has affected them deeply. While this psychological shift from love to hate to indifference is a necessary part of working toward the end of a secular bear, it is no fun for them — or anyone who trades or invests for a living.

3 Risk on/risk off: Let’s be brutally honest — the fundamentals have been utterly trumped by unprecedented central bank intervention. While this may be helping the wounded bank sector, it is not doing much for long-term investors in fixed income or equities. The Fed’s dual mandate of maximum employment and stable prices seems to have a newer unspoken goal: Driving risk asset prices higher.

When investors can no longer fashion a thesis other than “Buy when the Fed rolls out the latest bailout,” it takes a toll on psychology, and scares them away.

4 Poor returns across all asset classes: Investors have been burned by a series of booms and busts: dot-com stocks (2000); real estate (2006-?); equities (2008-09); even gold (2011-12) is significantly off its 2011 highs. Perhaps after these experiences, too many investors have decided that investing isn’t such a great deal after all.

5 De-leveraging: The marginal buyers are out of the market as they de-leverage excess credit consumption. There is an entire cohort of investors who are no longer playing with equities. Indeed, they have been priced out of all investment options as they rebuild their personal balance sheets.

6 Wall Street scandals (Part I): First the market gets blown up by bankers, and then Wall Street is rescued. Meantime, Main Street mostly got nothing but the invoice for the bailouts. If you don’t think the credit crisis and Great Recession have moved people to stay away from the casino, you are kidding yourself.

Many people believe the game is rigged against them. They aren’t conspiracy nuts, they are merely observing what has been going on since 2007. At the very least, it appears that bankers have corrupted the political process for their own gains. Investors are wondering why they should participate in such an absurd environment.

7 Trendless economy and markets: The economy has been operating just above stall speed. Manufacturing has been strong, employment has not, wages are flat and retail spending unremarkable. This soft economy does not get investors fired up about putting risk capital to work. And a range-bound market simply makes trading too challenging for most participants. Paying fees for zero returns, as we saw in 2011, isn’t very encouraging, either.

8 Bank scandals (Part II): Think about the recent scandals at various banks and investment firms. MF Global, Peregrine Financial, Knight Trading, Standard Charter and JPMorgan Chase — yet another set of factors that are persuading investors to stay away. Theft and incompetency appear rampant, and ethical transgressions seem to be part of ordinary business. Why on Earth should anyone entrust hard-earned money to those guys?

9 High frequency trading: Investing is a zero-sum game. The gains that the high-frequency traders have taken come right off the bottom line for anyone with a pension or retirement account. The complexity may be beyond the average investor’s comprehension, but the impact is not. People can smell when they are being ripped off, and you can blame the exchanges and high-frequency trades for that.

10 ETFs: Some people seem to have wised up to the stock-picking game. It was certainly fun while it was working during the rampaging bull market, but that has been over for years. When correlations go to 1, stock picking no longer matters. Add to that the advantages of lower costs, fees, taxes and turnovers, and the traditional stock-picking approach looks like a fool’s errand.

Does the average Main Street mom-and-pop investor think these things matter? I believe they do, and that is why so many investors have voted with their feet.

Lots of folks are wondering what happened to the Main Street-mom-and-pop retail investors. They seem to have taken their ball and gone home. I don’t blame them for feeling put upon, but it might be instructive to figure out why. Perhaps it could even help us determine what this means for risk capital.

We see evidence of this all over the place: The incredibly light volume of stock trading; the abysmal television ratings of CNBC; the closing of investing magazines such as Smart Money, whose final print issue is on newsstands as it transitions to a digital format; the dearth of stock chatter at cocktail parties. Why, it is almost as if America has fallen out of love with equities.

Given the events of the past decade and a half, this should come as no surprise. Average investors have seen not one but two equity collapses (2000 and 2008). They got caught in the real estate boom and bust. Accredited investors (i.e., the wealthier ones) also discovered that venture capital and private equity were no sure thing either. The Facebook IPO may have been the last straw.

What has driven the typical investor away from equities?

The short answer is that there is no single answer. It is complex, not reducible to single variable analysis. This annoys pundits who thrive on dumbing down complex and nuanced issues to easily digestible sound bites. Television is not particularly good at subtlety, hence the overwhelming tendency for shout-fests and silly bull/bear debates.

The factors that have been weighing on people-formerly-known-as-stock-investors are many. Consider the top 10 reasons investors are unenthused about the stock market:

1 Secular cycle: As we have discussed before, there are long-term cycles of alternating bull and bear markets. The current bear market that began in March 2000 has provided lots of ups and downs — but no lasting gains. Markets are effectively unchanged since 1999 (the Nasdaq is off only 40 percent from its 2000 peak).

The way secular bear markets end is with investors ignoring stocks, enormous P/E multiple compression and bargains galore. Bond king Bill Gross and his Death of the Cult of Equities is a good sign we are getting closer to the final denouement.

2 Psychology: Investors are scarred and scared. They have been scarred by the 57 percent crash in the major indexes from the 2007 peak to the 2009 bottom. They are scared to get back into equities because that is their most recent experience, and it has affected them deeply. While this psychological shift from love to hate to indifference is a necessary part of working toward the end of a secular bear, it is no fun for them — or anyone who trades or invests for a living.

3 Risk on/risk off: Let’s be brutally honest — the fundamentals have been utterly trumped by unprecedented central bank intervention. While this may be helping the wounded bank sector, it is not doing much for long-term investors in fixed income or equities. The Fed’s dual mandate of maximum employment and stable prices seems to have a newer unspoken goal: Driving risk asset prices higher.

When investors can no longer fashion a thesis other than “Buy when the Fed rolls out the latest bailout,” it takes a toll on psychology, and scares them away.

4 Poor returns across all asset classes: Investors have been burned by a series of booms and busts: dot-com stocks (2000); real estate (2006-?); equities (2008-09); even gold (2011-12) is significantly off its 2011 highs. Perhaps after these experiences, too many investors have decided that investing isn’t such a great deal after all.

5 De-leveraging: The marginal buyers are out of the market as they de-leverage excess credit consumption. There is an entire cohort of investors who are no longer playing with equities. Indeed, they have been priced out of all investment options as they rebuild their personal balance sheets.

6 Wall Street scandals (Part I): First the market gets blown up by bankers, and then Wall Street is rescued. Meantime, Main Street mostly got nothing but the invoice for the bailouts. If you don’t think the credit crisis and Great Recession have moved people to stay away from the casino, you are kidding yourself.

Many people believe the game is rigged against them. They aren’t conspiracy nuts, they are merely observing what has been going on since 2007. At the very least, it appears that bankers have corrupted the political process for their own gains. Investors are wondering why they should participate in such an absurd environment.

7 Trendless economy and markets: The economy has been operating just above stall speed. Manufacturing has been strong, employment has not, wages are flat and retail spending unremarkable. This soft economy does not get investors fired up about putting risk capital to work. And a range-bound market simply makes trading too challenging for most participants. Paying fees for zero returns, as we saw in 2011, isn’t very encouraging, either.

8 Bank scandals (Part II): Think about the recent scandals at various banks and investment firms. MF Global, Peregrine Financial, Knight Trading, Standard Charter and JPMorgan Chase — yet another set of factors that are persuading investors to stay away. Theft and incompetency appear rampant, and ethical transgressions seem to be part of ordinary business. Why on Earth should anyone entrust hard-earned money to those guys?

9 High frequency trading: Investing is a zero-sum game. The gains that the high-frequency traders have taken come right off the bottom line for anyone with a pension or retirement account. The complexity may be beyond the average investor’s comprehension, but the impact is not. People can smell when they are being ripped off, and you can blame the exchanges and high-frequency trades for that.

10 ETFs: Some people seem to have wised up to the stock-picking game. It was certainly fun while it was working during the rampaging bull market, but that has been over for years. When correlations go to 1, stock picking no longer matters. Add to that the advantages of lower costs, fees, taxes and turnovers, and the traditional stock-picking approach looks like a fool’s errand.

Does the average Main Street mom-and-pop investor think these things matter? I believe they do, and that is why so many investors have voted with their feet.

Saturday, 18 August 2012

The E&O price surge – and collapse

Good article in The Star by P. Gunasegaram, one of my favorite journalists, about the recent boom and bust in E&O's share price:

Nothing less than the integrity of our markets is at stake here. For too long, market manipulation and insider trading have been excused on the grounds that it makes the market, that it provides excitement and that it provides opportunities to make money for both traders and brokers.

But really, that's not the purpose of the market. The purpose is to provide a place where investors and others can seek a fair value for the assets they buy and sell through a fair, transparent and straightforward process that provides equal information and opportunity to all.

The economic aim for all that is to provide investors with a place to raise capital efficiently so that business can flourish.

It is lamentable that this basic aim of capital markets seems to be lost and it has become a place for wheelers, dealers and plain crooks to make money in less than honourable, and even illegal, ways.

What a shame! And will it ever change?

And I very much agree with that.

I would like to add two items to the discussion:

[1] The writer thinks that it is a quite clear case (based on previous ones) that Sime Darby does not need to make a mandatory general offer for the remaining shares. I think each case is different, and especially this one is intriguing. Two peculiar facts of this deal are that Sime Darby bought its shares at a high premium (60%), and that the sellers still have quite a few shares left. Together with each of the sellers, Sime Darby easily breaches the 33% rule.

[2] The writer does discuss the huge volume in E&O shares traded after the article on The Malaysian Insider was published, but there was also a huge volume in E&O call warrants. I have never liked these call warrants (they don't add any value to the economy), but the more so since it is unclear who the sellers are, retail investors who bought the warrants before, or bankers who still had inventory of them. I definetely hope that the trade in these warrants is also investigated by the authorities.

The E&O/Sime Darby saga will continue to hog the limelight for quite some time.

Nothing less than the integrity of our markets is at stake here. For too long, market manipulation and insider trading have been excused on the grounds that it makes the market, that it provides excitement and that it provides opportunities to make money for both traders and brokers.

But really, that's not the purpose of the market. The purpose is to provide a place where investors and others can seek a fair value for the assets they buy and sell through a fair, transparent and straightforward process that provides equal information and opportunity to all.

The economic aim for all that is to provide investors with a place to raise capital efficiently so that business can flourish.

It is lamentable that this basic aim of capital markets seems to be lost and it has become a place for wheelers, dealers and plain crooks to make money in less than honourable, and even illegal, ways.

What a shame! And will it ever change?

And I very much agree with that.

I would like to add two items to the discussion:

[1] The writer thinks that it is a quite clear case (based on previous ones) that Sime Darby does not need to make a mandatory general offer for the remaining shares. I think each case is different, and especially this one is intriguing. Two peculiar facts of this deal are that Sime Darby bought its shares at a high premium (60%), and that the sellers still have quite a few shares left. Together with each of the sellers, Sime Darby easily breaches the 33% rule.

[2] The writer does discuss the huge volume in E&O shares traded after the article on The Malaysian Insider was published, but there was also a huge volume in E&O call warrants. I have never liked these call warrants (they don't add any value to the economy), but the more so since it is unclear who the sellers are, retail investors who bought the warrants before, or bankers who still had inventory of them. I definetely hope that the trade in these warrants is also investigated by the authorities.

The E&O/Sime Darby saga will continue to hog the limelight for quite some time.

Friday, 17 August 2012

Australia is a Big Bubble

Astonishing article on the website of The Atlantic.

"Would you believe it if I told you that Australia's financial sector is worth more than the eurozone's financial sector? Well, it doesn't matter if you believe it or not. It's true. The technical term for this is "jaw-dropping." The chart below, from Cullen Roche of Pragmatic Capitalism, puts it all in rather stunning picture perspective."

Albert Edwards warned before about the biggest bubble in recent history in this article.

And thus is should not come as a surprise to see this kind of article:

"Australia’s sub prime mortgage scandal grows"

In April, we learned via the Australian newspaper how Australia’s largest banks are being forced to forgive mortgage debts of borrowers granted loans based on falsified or fraudulent information supplied by mortgage brokers.

Then in June, the Australian followed-up with further reports (here and here) of Australian sub-prime lending, and the battle playing-out between unscrupulous lenders and borrowers.

Now the Senate Inquiry into the post-GFC banking sector has revealed several instances of banks providing home loans to people who can’t afford them, and doctoring the paperwork so the loans looked okay. As well as allegations of widespread boosting in loan approvals.

Perhaps the most shocking of the revelations are instances where the banks have been enticing elderly Australians into Ponzi-like mortgages that they had no way of repaying.

Has the World learned anything from the 2008/2009 Global Financial Crisis? It doesn't look like it.

Real estate and banks in Australia appear to be in bubble territory, European shares might be a contrarian play. European banks appear cheap (although risky), Marc Faber recommends to buy selected European telecom players, who have fallen tremendously in value since 2000. The richest man in the world, Mexican Carlos Slim also has his eye on this group of companies.

"Would you believe it if I told you that Australia's financial sector is worth more than the eurozone's financial sector? Well, it doesn't matter if you believe it or not. It's true. The technical term for this is "jaw-dropping." The chart below, from Cullen Roche of Pragmatic Capitalism, puts it all in rather stunning picture perspective."

Albert Edwards warned before about the biggest bubble in recent history in this article.

- Because Australia has gone so long without a recession, everyone has been convinced that it's managed by geniuses, and that the economy there is solved. This is classic bubble thinking.

- But Australia has telltale signs of a bubble.

- 5 of the world's most expensive cities are now in Australia (Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Brisbane, and Perth).

- Not one Australian city falls into traditional measures of "affordability."

- The entire Australian economy is premised on the wheels not coming off China.

Our own more Minskyan interpretation of events is that the lack of volatility in the Australian economic cycle and the absence of any recession since 1991 has led Australians to have an excessive appetite for debt in the belief the future will reflect the past. But for us, suppressed volatility is merely storing up an even bigger crash further down the road.

"Australia’s sub prime mortgage scandal grows"

In April, we learned via the Australian newspaper how Australia’s largest banks are being forced to forgive mortgage debts of borrowers granted loans based on falsified or fraudulent information supplied by mortgage brokers.

Then in June, the Australian followed-up with further reports (here and here) of Australian sub-prime lending, and the battle playing-out between unscrupulous lenders and borrowers.

Now the Senate Inquiry into the post-GFC banking sector has revealed several instances of banks providing home loans to people who can’t afford them, and doctoring the paperwork so the loans looked okay. As well as allegations of widespread boosting in loan approvals.

Perhaps the most shocking of the revelations are instances where the banks have been enticing elderly Australians into Ponzi-like mortgages that they had no way of repaying.

Has the World learned anything from the 2008/2009 Global Financial Crisis? It doesn't look like it.

Real estate and banks in Australia appear to be in bubble territory, European shares might be a contrarian play. European banks appear cheap (although risky), Marc Faber recommends to buy selected European telecom players, who have fallen tremendously in value since 2000. The richest man in the world, Mexican Carlos Slim also has his eye on this group of companies.

Tuesday, 14 August 2012

Monday, 13 August 2012

BRDB, who is behind 33% of the shares?

From an article in The Edge of August 6, 2012, written by M. Shanmugam:

"As far back as November last year, the writing was on the wall that Ambang Sehati Sdn Bhd, the major shareholder of Bandar Raya Development Bhd (BRDB) would be forced to privatise the property developer.

A poorly orchestrated bid by the private company to carve out a clutch of prime properties held by BRDB for RM 914 million triggered protests from the minority shareholders and forced the directors of the publicly listed company to invite competing bids for the assets - the retail centre in Capital Square, Permas Jaya Mall and BR Property Holdings Sdn Bhd.

The prospect of an auction left Ambang Sehati with no choice but to launch a takeover of the company, financial executives say".

"Ambang Sehati has an 18.84% stake in BRDB and plays second fiddle to a group of investors whose shares are held by Credit Suisse in two blocks totalling 33.18%.

The ultimate owner of the 33.18% is not known....."

I left out on purpose the speculation who possibly owns this block. I don't think minority shareholders should have to guess who actually controls a company. Knowledge who owns and controls large amounts of shares is very important from a corporate governance point of view. It has far reaching implications for instance towards related party transactions, possible mandatory general offers, parties acting in concert, voting in AGM's and EGM's, etc.

The Malaysian authorities should force the holders of the large block of shares to reveal themselves. Their inaction in this matter is puzzling, to say the least.

"As far back as November last year, the writing was on the wall that Ambang Sehati Sdn Bhd, the major shareholder of Bandar Raya Development Bhd (BRDB) would be forced to privatise the property developer.

A poorly orchestrated bid by the private company to carve out a clutch of prime properties held by BRDB for RM 914 million triggered protests from the minority shareholders and forced the directors of the publicly listed company to invite competing bids for the assets - the retail centre in Capital Square, Permas Jaya Mall and BR Property Holdings Sdn Bhd.

The prospect of an auction left Ambang Sehati with no choice but to launch a takeover of the company, financial executives say".

"Ambang Sehati has an 18.84% stake in BRDB and plays second fiddle to a group of investors whose shares are held by Credit Suisse in two blocks totalling 33.18%.

The ultimate owner of the 33.18% is not known....."

I left out on purpose the speculation who possibly owns this block. I don't think minority shareholders should have to guess who actually controls a company. Knowledge who owns and controls large amounts of shares is very important from a corporate governance point of view. It has far reaching implications for instance towards related party transactions, possible mandatory general offers, parties acting in concert, voting in AGM's and EGM's, etc.

The Malaysian authorities should force the holders of the large block of shares to reveal themselves. Their inaction in this matter is puzzling, to say the least.

Friday, 10 August 2012

SC to order Sime general offer for E&O?

Interesting article on the Malaysian Insider website suggesting that Sime Darby has to make a general offer for E&O shares after all.

The crux of the matter: "A general offer can also be triggered if a new party buys less than 33 per cent but secures management control of the target company".

However, according to an article on the website of The Star

Sime Darby Bhd does not have to make a general offer for the remaining shares in Eastern and Oriental Holdings (E&O) after it acquired a 30% stake, according to the Securities Commission.

The SC said in a statement on Friday that its position on the GO requirement in the Sime Darby-E&O acquisition remained unchanged as per the statement issued on Oct 11, last year.

"The decision is now subject to judicial review which is pending in court," the SC said.

Securities of E&O surged in active trade late Friday on a news portal report that the SC would now order Sime Darby to make a GO for the remaining E&O shares.

Above is today's chart, the share price of E&O is up RM 0.42 in very heavy volume, the warrant is up a whopping 3,199%, also in very heavy volume.

Looks like the authorities have another possible case of insider trading to deal with since there has been no official announcement.

Article from Malaysian Insider:

In a volte face (Wiki: a total change of position, as in policy or opinion; an about-face), the Securities Commission (SC) will now order Sime Darby Bhd to make a general offer for Eastern & Oriental Bhd (E&O) shares after buying a 30-per cent stake last year, say government sources.

The Malaysian Insider understands the decision was made after a review by the leadership under new SC chairman Datuk Ranjit Ajit Singh.

“The SC has reviewed the matter and decided to overturn the earlier decision made when Tan Sri Zarinah Anwar was the chairman,” a government source told The Malaysian Insider.

Ranjit, who was the SC managing director, took over as chairman after Zarinah ended her term last March 31.

Another source confirmed the review and said the decision will be made public soon.

Sime Darby purchased its controlling 30 per cent interest in the property developer from three major shareholders — managing director Datuk Terry Tham, Singapore’s GK Goh Holdings and a group of investors led by businessman Tan Sri Wan Azmi Wan Hamzah — at the end of August last year in a deal that valued E&O shares at RM2.30 a piece.

The purchase price represented a 60 per cent premium over the value of the shares in the company on the open market when the deal was announced.

The RM776 million deal triggered unease over the widely-perceived coddling by the agency of large state-controlled companies at the expense of minority shareholders when exercising its authority on corporate takeovers.

The SC ruled six weeks after Sime Darby’s purchase of the three blocks that the plantation-based conglomerate need not make a general offer, prompting E&O minority shareholder Michael Chow to sue the SC for failing to compel Sime Darby to make a general offer for the rest of the shares.

The legal suit has renewed debate over the SC’s handling of alleged irregular trading activities and had put pressure on Zarinah, whose husband — the E&O chairman — had raised his personal stock holdings in the company just weeks before Sime Darby announced the acquisition.

The SC has also filed an application to recuse the judge hearing the suit as he used to be with the regulator. But the judge dismissed the application, only for the SC to file an appeal with the Court of Appeal, which heard the case yesterday.

Singapore’s Straits Times reported last January that a SC task force found that Sime Darby was obliged to make a general offer for E&O shares after acquiring a 30 per but was superseded by the regulator’s top ruling authority.

The daily reported that the task force was of the view that a general offer obligation had been triggered as a new “concert party” was created between Sime Darby and Tham, who jointly controlled more than 33 per cent in the property concern after the deal.

Malaysia’s takeover rules stipulate that any party that acquires more than a 33 per cent interest in a publicly-listed entity must carry out a general offer for the remaining shares.

A general offer can also be triggered if a new party buys less than 33 per cent but secures management control of the target company.

But the SC’s final ruling three-member committee adjudged “in a majority decision” that there was no general offer obligation as Sime Darby and Tham were not acting in concert, according to an affidavit by the agency’s second-most senior commissioner Datuk Francis Tan, which was sighted by the Singapore daily.

The committee also accepted the task force’s recommendation that the three groups that sold the blocks of E&O shares to Sime Darby did not collectively control the company and that the disposal did not trigger a general offer.

The crux of the matter: "A general offer can also be triggered if a new party buys less than 33 per cent but secures management control of the target company".

However, according to an article on the website of The Star

Sime Darby Bhd does not have to make a general offer for the remaining shares in Eastern and Oriental Holdings (E&O) after it acquired a 30% stake, according to the Securities Commission.

The SC said in a statement on Friday that its position on the GO requirement in the Sime Darby-E&O acquisition remained unchanged as per the statement issued on Oct 11, last year.

"The decision is now subject to judicial review which is pending in court," the SC said.

Securities of E&O surged in active trade late Friday on a news portal report that the SC would now order Sime Darby to make a GO for the remaining E&O shares.

Above is today's chart, the share price of E&O is up RM 0.42 in very heavy volume, the warrant is up a whopping 3,199%, also in very heavy volume.

Looks like the authorities have another possible case of insider trading to deal with since there has been no official announcement.

Article from Malaysian Insider:

In a volte face (Wiki: a total change of position, as in policy or opinion; an about-face), the Securities Commission (SC) will now order Sime Darby Bhd to make a general offer for Eastern & Oriental Bhd (E&O) shares after buying a 30-per cent stake last year, say government sources.

The Malaysian Insider understands the decision was made after a review by the leadership under new SC chairman Datuk Ranjit Ajit Singh.

“The SC has reviewed the matter and decided to overturn the earlier decision made when Tan Sri Zarinah Anwar was the chairman,” a government source told The Malaysian Insider.

Ranjit, who was the SC managing director, took over as chairman after Zarinah ended her term last March 31.

Another source confirmed the review and said the decision will be made public soon.

Sime Darby purchased its controlling 30 per cent interest in the property developer from three major shareholders — managing director Datuk Terry Tham, Singapore’s GK Goh Holdings and a group of investors led by businessman Tan Sri Wan Azmi Wan Hamzah — at the end of August last year in a deal that valued E&O shares at RM2.30 a piece.

The purchase price represented a 60 per cent premium over the value of the shares in the company on the open market when the deal was announced.

The RM776 million deal triggered unease over the widely-perceived coddling by the agency of large state-controlled companies at the expense of minority shareholders when exercising its authority on corporate takeovers.

The SC ruled six weeks after Sime Darby’s purchase of the three blocks that the plantation-based conglomerate need not make a general offer, prompting E&O minority shareholder Michael Chow to sue the SC for failing to compel Sime Darby to make a general offer for the rest of the shares.

The legal suit has renewed debate over the SC’s handling of alleged irregular trading activities and had put pressure on Zarinah, whose husband — the E&O chairman — had raised his personal stock holdings in the company just weeks before Sime Darby announced the acquisition.

The SC has also filed an application to recuse the judge hearing the suit as he used to be with the regulator. But the judge dismissed the application, only for the SC to file an appeal with the Court of Appeal, which heard the case yesterday.

Singapore’s Straits Times reported last January that a SC task force found that Sime Darby was obliged to make a general offer for E&O shares after acquiring a 30 per but was superseded by the regulator’s top ruling authority.

The daily reported that the task force was of the view that a general offer obligation had been triggered as a new “concert party” was created between Sime Darby and Tham, who jointly controlled more than 33 per cent in the property concern after the deal.

Malaysia’s takeover rules stipulate that any party that acquires more than a 33 per cent interest in a publicly-listed entity must carry out a general offer for the remaining shares.

A general offer can also be triggered if a new party buys less than 33 per cent but secures management control of the target company.

But the SC’s final ruling three-member committee adjudged “in a majority decision” that there was no general offer obligation as Sime Darby and Tham were not acting in concert, according to an affidavit by the agency’s second-most senior commissioner Datuk Francis Tan, which was sighted by the Singapore daily.

The committee also accepted the task force’s recommendation that the three groups that sold the blocks of E&O shares to Sime Darby did not collectively control the company and that the disposal did not trigger a general offer.

Thursday, 9 August 2012

Amin Shah and the Singapore-Batam ferry

From time to time two parties fight it out in the court room, a good moment for outsiders to get a glimpse of what is going on behind the Malaysian scenes.

In Singapore, a judgment has been made on August 3, 2012, in a case between Chenet Finance Ltd and (Allene) Lim Poh Yen and others. This article can be found on the website of the Singapore Law Watch. The article is 82 pages, and it will be revealing what was all going on in this case. I recommend the reader first to skip to page 78-80, for a description of the people and companies involved.

Berlian’s main business is the operation of the ferry route between HarbourFront Centre in Singapore and Harbour Bay Terminal in Batam (an island of the Republic of Indonesia), over which it enjoys a monopoly.

The shareholders of Berlian are Chenet (88.9%), Abu Bakar (9.6%) and others (1.5%).

It was not really disputed that Chenet acts on the wishes of Amin Shah, irrespective of the true identity to the beneficial owner of Chenet, although Eranur Shahda ("Eranur"), Amin Shah’s daughter, sought to suggest that an uncle was in control of the Trust together with Amin Shah.

At Amin Shah’s behest, his good friend and fellow Malaysian businessman Andrew Lee Choong Lim ("Andrew Lee") further injected a sum of $2.5m into Berlian, and also assumed its debts of $1.8m. In return, Andrew Lee received 55% of Berlian’s shares. However, at that time, Andrew Lee did not wish to hold the Berlian shares in his own name, so he accepted Amin Shah’s recommendation of a loyal servant – Abu Bakar – to act as his nominee. According to Amin Shah, that was how Abu Bakar, a man of little means, came to hold those shares registered in his name, and that also explained why he was made the Chairman and a director of Berlian. Abu Bakar was further made a guarantor for the loan.

Sometime in early 2009, Amin Shah decided that Chenet should transfer the Shares to Hopaco, a company owned by Andrew Lee. The idea was that Andrew Lee’s high net worth would be enough to comfort Caterpillar. The initial plan devised in early May 2009 by Amin Shah’s Malaysian lawyer Thanggaya was to have a loan agreement under which Hopaco would purportedly lend $2.2m to Chenet, with the Shares acting as security.

The loan agreement would be backdated to 19 April 2007 and Chenet would then "default" on the loan in 2009, resulting in the transfer of the Shares to Hopaco.

Court: [The transfer to Hopaco] is not supposed to be a true transaction, it was meant to be a sham transaction because Hopaco is not supposed to be the real owner of the shares. It’s just supposed to show to Caterpillar that now one of our shareholders is Hopaco, who has got a high net worth individual, [Andrew Lee].

A: Yes.

Court: So even this 2.2 million deal is not really meant for Hopaco to acquire the shares, but it’s just a sham to satisfy Caterpillar’s enquiry.

A: Yes.

When questioned about where he had got the RM1m from, he answered that the money was from his profits from brokering contracts through his political contacts.

He also started two other companies – Integrated Maker Sdn Bhd in 1993, with a paid up capital of RM1m; and Integrated Steel Industries Sdn Bhd in 2000, with a paid up capital of around RM20m.

In Singapore, a judgment has been made on August 3, 2012, in a case between Chenet Finance Ltd and (Allene) Lim Poh Yen and others. This article can be found on the website of the Singapore Law Watch. The article is 82 pages, and it will be revealing what was all going on in this case. I recommend the reader first to skip to page 78-80, for a description of the people and companies involved.

Shares held on other people's names, a "sham transaction", a valuation that didn't make any sense at all, a former mistress, a bankrupt, a BVI company, and even allegations of physical and verbal abuse and money laundering.

Needless, to say, something was bound to go wrong, and that was exactly what happened. A messy affair, giving the readers a rare opportunity to peek in this world of business.

Some snippets:

Berlian’s main business is the operation of the ferry route between HarbourFront Centre in Singapore and Harbour Bay Terminal in Batam (an island of the Republic of Indonesia), over which it enjoys a monopoly.

Each of the defendants alleges that the true beneficial owner of Chenet is Tan Sri Amin Shah ("Amin Shah").

Amin Shah was made a bankrupt in Malaysia by order of court on 9 October 2007.

Chenet gave notice to Berlian that it wished to transfer the Shares to Hopaco for $2.2m (a rather surprising valuation, since the net profit in 2008 was $5.8m, an accountant valued the company in 2011 on $15.8 million).

Sometime in early 2009, Amin Shah decided that Chenet should transfer the Shares to Hopaco, a company owned by Andrew Lee. The idea was that Andrew Lee’s high net worth would be enough to comfort Caterpillar. The initial plan devised in early May 2009 by Amin Shah’s Malaysian lawyer Thanggaya was to have a loan agreement under which Hopaco would purportedly lend $2.2m to Chenet, with the Shares acting as security.

The loan agreement would be backdated to 19 April 2007 and Chenet would then "default" on the loan in 2009, resulting in the transfer of the Shares to Hopaco.

Eranur (Amin Shah's daughter) admitted on the witness stand that it was not meant to be a genuine transfer:

Court: [The transfer to Hopaco] is not supposed to be a true transaction, it was meant to be a sham transaction because Hopaco is not supposed to be the real owner of the shares. It’s just supposed to show to Caterpillar that now one of our shareholders is Hopaco, who has got a high net worth individual, [Andrew Lee].

Abu Bakar accepted that he had once worked as a technician with the Federal Employee’s Provident Fund (EPF) for a salary of RM1,000/month.

Abu Bakar gave evidence of companies which he had incorporated. The first, Atlantic Range Sdn Bhd, was incorporated in 1991 with a paid up capital of RM1m.When questioned about where he had got the RM1m from, he answered that the money was from his profits from brokering contracts through his political contacts.

Sunday, 5 August 2012

Malaysian oil statistics are puzzling

Claire Barnes wrote in the second quarter report of the Apollo Asia Fund about the puzzling revision in Malaysian oil statistics: The imprecision of vital statistics.

I recommend the reader to read the full article, here are some parts of it:

There has been much recent discussion of Chinese statistics, but I have seen none at all on an interesting revision to BP's data on Malaysian oil production and consumption. BP's annual 'Statistical Review of World Energy' has become a principal source of information on primary energy trends: the latest version may be found at www.bp.com. The Energy Export Databrowser provides helpful charts based on this data.

Compare the chart on the left, based on data in BP's 2010 review, with that on the right, based on its latest review:

These charts, and many others, can be found on this website: Energy Export Databrowser

The earlier chart shows Malaysia's oil production on a plateau since 1995, consumption levelling out since 2002, and a gradual reduction in net exports. The chart from the latest data shows a much more alarming picture: falling production, a continued rise in consumption, and a rapid collapse of net exports.

Without BP's recent data revisions, the decline in net exports would be less steep, but still significant. The issue is surely of huge importance to the economy, the government budget, and the patronage machine. One would expect such issues to feature prominently in public debate, but there is little awareness or discussion. To some extent, growing demand reflects an attempt to add value locally rather than exporting raw commodities - but is this always a wise use of a dwindling resource? There are some moves to phase out energy subsidies by gradual increases in gas prices to industrial users, but no apparent Plan B for what happens if the market price continues to outpace the planned increases. Fuel and electricity prices are politically sensitive, so no rational discussion occurs, and profligacy continues. Meanwhile, moves to encourage development of Malaysia's marginal fields seem sensible, but are they likely to stem the decline?

Indonesia became a net importer of oil several years ago, and its oil-and-gas production peaked in 1997, but the remarkable growth in coal output has led to a continued rise in primary energy output and net exports (right hand chart above). While the coal mining sector has received plenty of attention from investors, it is interesting that the decline in primary energy exports from 1996 to 2003 coincided with a period of very poor performance for the Indonesian stock market, and the subsequent surge in primary energy exports has coincided with the prolonged boom.

Energy policy in Indonesia is certainly no more coherent than in Malaysia, but the musings of ministers do at least range more broadly, which may perhaps allow hope for change. Indonesia, Malaysia and India suffer from the distortions and misallocations caused by energy subsidies: reforming these would be a good place to start.

Postscript 18 July:

The spreadsheet has been expanded with data from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA, www.eia.gov) and from the Joint Organisations Data Initiative (JODI), which broadly agree with the current BP picture of a rapid decline in Malaysia's oil production. JODI and Bank Negara both give monthly statistics, and JODI's show a much steeper decline

BP's consumption figures are for a broader range of products than its production figures. Its world oil consumption figures exceed its production figures by a growing margin, as shown in this blog post. Nevertheless, the revisions to production and consumption for Malaysia are unusually large, and remain unexplained. One guess is that a shift from net exports to net imports is more visible to the market than a mere change in net export level, and that the statisticians then have to reconcile their historic figures with the new facts while avoiding the assumption of too drastic a change in one year. While statistical details remain unclear, this affects only timing. The long view already provides cause for concern, but this may be playing out faster than expected.

The fat years for Malaysia were between 1983 and 2005, when production (grey) clearly outpaced consumption (black line), resulting in a large net export (green) of about 10 million tonnes per year. The price of oil was about USD 20 per barrel during those years.

Between 2005 and 2010 the net exports dwindled to about 5 million tonnes per year. But this was more than offset by the rising oil price which hovered around USD 70 per barrel.

The fat years are over, and Malaysia has turned into a net oil importer. With global oil consumption on the rise, I expect the price in the long run only to rise further. In other words, Malaysia has been exporting oil for decades at a price around USD 20 per barrel, and might have to import oil in the future at a price that is five or ten times that price. Instead of growing a piggybank for the more lean times (like Norway has done), Malaysia's government did choose to run budget deficits for years in a row.

Luckily for Malaysia, it is still a net exporter in gas, although production seems to have slowed down a bit in recent years:

I recommend the reader to read the full article, here are some parts of it:

There has been much recent discussion of Chinese statistics, but I have seen none at all on an interesting revision to BP's data on Malaysian oil production and consumption. BP's annual 'Statistical Review of World Energy' has become a principal source of information on primary energy trends: the latest version may be found at www.bp.com. The Energy Export Databrowser provides helpful charts based on this data.

Compare the chart on the left, based on data in BP's 2010 review, with that on the right, based on its latest review:

The earlier chart shows Malaysia's oil production on a plateau since 1995, consumption levelling out since 2002, and a gradual reduction in net exports. The chart from the latest data shows a much more alarming picture: falling production, a continued rise in consumption, and a rapid collapse of net exports.

2011 was a poor year for Malaysian oil production, due partly to temporary factors. Bank Negara reported a 10.7% decline (v BP's 10.9%) and attributed it to 'shutdowns of several production facilities for maintenance purposes, declining production from mature fields, and lower-than-expected production from new fields'. The trends in recent years are comparable in the two sets of statistics. Unexplained are the major revisions to BP's historic data series. Over the last two years, BP has revised downward the production figures back to 1984, but particularly since 1995; and revised upwards the consumption figures since 1994, but by escalating amounts since 2000, particularly since 2006. Unfortunately, 'BP regrets it is unable to deal with enquiries about the data', and we cannot find current consumption figures in any Malaysian source.

Malaysia's decades of prosperity have coincided with a great energy windfall. When oil production ceased to grow, gas production continued to soar - but that has now ceased. The chart on the left suggests the magnitude of the changes which may now be under way. It is based on the latest BP review, and includes figures for hydropower (small) and biofuels (insignificant). According to BP, Malaysia's primary energy production, in million tonnes oil equivalent, peaked in 2008: three years later, it was down 9%. Malaysia's primary energy consumption continued to rise until 2010 - but in 2011, gas shortages began to bite in the Peninsula; BP shows domestic gas consumption down 10.5% for the year. Net primary energy exports peaked in 1999; they are since down 54%.

(for primary energy charts see original article)

Without BP's recent data revisions, the decline in net exports would be less steep, but still significant. The issue is surely of huge importance to the economy, the government budget, and the patronage machine. One would expect such issues to feature prominently in public debate, but there is little awareness or discussion. To some extent, growing demand reflects an attempt to add value locally rather than exporting raw commodities - but is this always a wise use of a dwindling resource? There are some moves to phase out energy subsidies by gradual increases in gas prices to industrial users, but no apparent Plan B for what happens if the market price continues to outpace the planned increases. Fuel and electricity prices are politically sensitive, so no rational discussion occurs, and profligacy continues. Meanwhile, moves to encourage development of Malaysia's marginal fields seem sensible, but are they likely to stem the decline?

Energy policy in Indonesia is certainly no more coherent than in Malaysia, but the musings of ministers do at least range more broadly, which may perhaps allow hope for change. Indonesia, Malaysia and India suffer from the distortions and misallocations caused by energy subsidies: reforming these would be a good place to start.

Postscript 18 July:

The spreadsheet has been expanded with data from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA, www.eia.gov) and from the Joint Organisations Data Initiative (JODI), which broadly agree with the current BP picture of a rapid decline in Malaysia's oil production. JODI and Bank Negara both give monthly statistics, and JODI's show a much steeper decline

BP's consumption figures are for a broader range of products than its production figures. Its world oil consumption figures exceed its production figures by a growing margin, as shown in this blog post. Nevertheless, the revisions to production and consumption for Malaysia are unusually large, and remain unexplained. One guess is that a shift from net exports to net imports is more visible to the market than a mere change in net export level, and that the statisticians then have to reconcile their historic figures with the new facts while avoiding the assumption of too drastic a change in one year. While statistical details remain unclear, this affects only timing. The long view already provides cause for concern, but this may be playing out faster than expected.

The fat years for Malaysia were between 1983 and 2005, when production (grey) clearly outpaced consumption (black line), resulting in a large net export (green) of about 10 million tonnes per year. The price of oil was about USD 20 per barrel during those years.

Between 2005 and 2010 the net exports dwindled to about 5 million tonnes per year. But this was more than offset by the rising oil price which hovered around USD 70 per barrel.

The fat years are over, and Malaysia has turned into a net oil importer. With global oil consumption on the rise, I expect the price in the long run only to rise further. In other words, Malaysia has been exporting oil for decades at a price around USD 20 per barrel, and might have to import oil in the future at a price that is five or ten times that price. Instead of growing a piggybank for the more lean times (like Norway has done), Malaysia's government did choose to run budget deficits for years in a row.

Luckily for Malaysia, it is still a net exporter in gas, although production seems to have slowed down a bit in recent years:

Saturday, 4 August 2012

Short-termism is a fundamental problem in equity markets

Interesting Article by Andrew Sheng in The Star today:

"Do stock markets serve investors?

Some snippets:

In the wake of the current crisis, the British government invited LSE Prof John Kay to review the UK equity market and its impact on the governance of UK-listed companies. The report was published on July 23 and has many lessons on the theory and practice of Asian stock markets.