Article from The Malaysian Insider:

Debt-laden 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) insisted today its accounts are audited by an international firm, saying it reserves the right to sue those making malicious and slanderous statements against the government-owned strategic investor.

The company broke its silence after senior banker Datuk Seri Nazir Razak yesterday told its board to appoint independent auditors or resign over a RM42 billion debt. "

The Board would like to stress that 1MDB accounts are audited by an international audit firm, Deloitte, " it said in a statement issued in capital Kuala Lumpur tonight.

It said that Deloitte signed off 1MDB’s 2013 and 2014 accounts without qualification and similarly KPMG signed off the 2010, 2011 and 2012 accounts with no qualification.

Accounts audited by international audit firms, members of the "Big Four".

What possibly could go wrong?

Well, let's start with "The dozy watchdogs" written by The Economist, some snippets:

PwC’s failure to detect the problem is hardly an isolated case. If accounting scandals no longer dominate headlines as they did when Enron and WorldCom imploded in 2001-02, that is not because they have vanished but because they have become routine. On December 4th a Spanish court reported that Bankia had misstated its finances when it went public in 2011, ten months before it was nationalised. In 2012 Hewlett-Packard wrote off 80% of its $10.3 billion purchase of Autonomy, a software company, after accusing the firm of counting forecast subscriptions as current sales (Autonomy pleads innocence). The previous year Olympus, a Japanese optical-device maker, revealed it had hidden billions of dollars in losses. In each case, Big Four auditors had given their blessing.

And although accountants have largely avoided blame for the financial crisis of 2008, at the very least they failed to raise the alarm. America’s Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation is suing PwC for $1 billion for not detecting fraud at Colonial Bank, which failed in 2009. (PwC denies wrongdoing and says the bank deceived the firm.) This June two KPMG auditors received suspensions for failing to scrutinise loan-loss reserves at TierOne, another failed bank. Just eight months before Lehman Brothers’ demise, EY’s audit kept mum about the repurchase transactions that disguised the bank’s leverage.

The situation is graver still in emerging markets. In 2009 Satyam, an Indian technology company, admitted it had faked over $1 billion of cash on its books. North American exchanges have de-listed more than 100 Chinese firms in recent years because of accounting problems. In 2010 Jon Carnes, a short seller, sent a cameraman to a biodiesel factory that China Integrated Energy (a KPMG client) said was producing at full blast, and found it had been dormant for months. The next year Muddy Waters, a research firm, discovered that much of the timber Sino-Forest (audited by EY) claimed to own did not exist. Both companies lost over 95% of their value.

Of course, no police force can hope to prevent every crime. But such frequent scandals call into question whether this is the best the Big Four can do—and if so, whether their efforts are worth the $50 billion a year they collect in audit fees. In popular imagination, auditors are there to sniff out fraud. But because the profession was historically allowed to self-regulate despite enjoying a government-guaranteed franchise, it has set the bar so low—formally, auditors merely opine on whether financial statements meet accounting standards—that it is all but impossible for them to fail at their jobs, as they define them. In recent years this yawning “expectations gap” has led to a pattern in which investors disregard auditors and make little effort to learn about their work, value securities as if audited financial statements were the gospel truth, and then erupt in righteous fury when the inevitable downward revisions cost them their shirts.

The modern audit does not even provide an opinion on accuracy. Instead, the boilerplate one-page pass/fail report in America merely provides “reasonable assurance” that a company’s statements “present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of [the company] in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)”. GAAP is a 7,700-page behemoth, packed with arbitrary cut-offs and wide estimate ranges, and riddled with loopholes so big that some accountants argue even Enron complied with them. (International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), which are used outside the United States, rely more on broad principles). “An auditor’s opinion really says, ‘This financial information is more or less OK, in general, so far as we can tell, most of the time’,” says Jim Peterson, a former lawyer for Arthur Andersen, the now-defunct accounting firm that audited Enron. “Nobody has paid any attention or put real value on it for about 30 years.”

Those conflicts of interest

Even so, the misaligned incentives built into auditing all but guarantee that accountants will fall short of investors’ needs. The beneficiaries of the service—current and prospective shareholders—pay for it indirectly or not at all, while the purchasers buy it only because they are required to. As a result, companies tend to select auditors who will provide a clean opinion as cheaply and quickly as possible. Similarly, accountants who discover irregularities may be better off asking management to make minor adjustments, rather than blowing the whistle on a misstatement that could embroil their firm in costly litigation.

I invite the reader to Google on search terms like "Deloitte" "accounting" "scandals" or "KPMG" "accounting" "scandals", and one would see a huge list of incidents regarding these two audit firms. PwC or EY , the other companies in the "Big Four" don't seem to be any better, for that matter.

A Blog about [1] Corporate Governance issues in Malaysia and [2] Global Investment Ideas

Showing posts with label KPMG. Show all posts

Showing posts with label KPMG. Show all posts

Friday, 15 May 2015

Saturday, 12 April 2014

Maybulk: IPO of POSH (4)

The prospectus for the coming EGM of Maybulk contains an independent advice of KPMG Malaysia.

This is the same adviser who wrote the independent advice in 2008, about which I wrote before, in rather harsh terms.

The current advice is much better. Cynics will say that it would have been very hard to do a worse job than the one in 2008. It is also in line with a (belated) general improvement of independent advice across the board for Bursa listed companies.

There are some interesting parallels with 2008, although unfortunately KPMG doesn't revisit the 2008 report.

Regarding the PAT of POSH, the following graph is presented:

Looks rather convincingly, doesn't it?

But there is an eerie similarity with the picture presented in 2008:

The last column is based on only 9 months, the full 12 month result would be USD 81M, while the company made a PAT of USD 88M in 2009.

The rather strange fact (which isn't mentioned at all in the 2014 report) is that POSH made a higher profit in 2008 and 2009 than each year after that, despite:

This was what KPMG wrote in 2008:

The results of 2008 were more or less known in December 2008, so let's compare those with the results of 2011 and 2012, the timeline that KPMG indicated in the above paragraph.

It turns out those profits were only USD 26M (2011) and USD 54M (2012), a whopping 68% and 33% lower than the profit in 2008, while KPMG forecasted "substantial growth over the next three to four years".

So much for the rather poor forecasting capabilities of KPMG. And they can't blame the global recession for that, the acquisition of POSH by Maybulk in 2008 was right smack in the middle of it.

For the benefit of the reader, the full earnings picture of POSH, all amounts in USD:

2006: 0M (company just started)

2007: 9M (first acquisitions, paid-up still very low)

2008: 81M (injection 160M from PCL, 221M from Maybulk)

2009: 88M

2010: 28M

2011: 26M

2012: 54M (rights issue of 150M)

2013: 73M

Is this indeed a "track record of strong financial performance", as is claimed in the 2014 prospectus by the Chairman? Based on the last three years results, may be. Based on the last six years not really, I think.

Return on Equity in the last three years was 4.6%, 9.0% and 11.1% despite being rather leveraged, not impressive.

There doesn't seem to be growth in revenue over the last three years. Most of the growth in profit comes from "Other operating income", not sure how recurring those are (below numbers have not yet been adjusted downwards):

Another interesting topic is the valuation by KPMG, this is the current one:

This is the valuation of 2008 based on adjusted NA:

And their valuation of 2008 based on DCF:

What is remarkable is that the valuations of 2008 and 2014 are almost identical, while:

The only way to explain the peculiar valuations is to assume that KPMG's valuation of POSH in 2008 was simply much too high, unrealistically so.

For one part (the DCF valuation), KPMG should fully take the blame.

For the Asset valuation, that was partly based on the valuation of Clarkson, about which I wrote under the title: "Clarkson, the valuer who didn’t believe his own valuation".

That title was indeed deemed to be correct (the authorities have confirmed that), the valuation of Clarkson was made on September 15, 2008 and was not valid on the day the prospectus was issued, November 25, 2008. In only a bit more than two months time values of vessels had collapsed, like almost all other asset values, making the valuation much too high.

The important question is: why did nobody question the valuation of Clarkson?

There are many maritime experts in the board of directors of Maybulk, POSH and PCL who should have known about the problems in this industry.

But even the non-maritime experts of those boards of directors, the writers of the prospectus AmInvestment Bank and the independent adviser KPMG, they should have guessed that the valuation might not be correct anymore, and should have actively sought clarification.

Why did no one contact Clarkson at the end of November or early December 2008? They were just one single phone call or email away.

A new, updated valuation by Clarkson would have had a huge impact on the adjusted net assets, the more since POSH was highly geared.

And that would have enabled the non-interested directors of Maybulk to renegotiate a much fairer deal for the shareholders of Maybulk.

Maybulk's shareholders deserved a much larger chunk of POSH in exchange for its large injection in POSH, in my opinion roughly 50% of the shares instead of the 21% it would receive. Profit contributions in the subsequent years would then have made a much higher impact, and at the coming IPO of POSH Maybulk would not need to buy additional shares to keep a minimum shareholding of 20%, it could even consider selling some shares, if the price is right.

This is the same adviser who wrote the independent advice in 2008, about which I wrote before, in rather harsh terms.

The current advice is much better. Cynics will say that it would have been very hard to do a worse job than the one in 2008. It is also in line with a (belated) general improvement of independent advice across the board for Bursa listed companies.

There are some interesting parallels with 2008, although unfortunately KPMG doesn't revisit the 2008 report.

Regarding the PAT of POSH, the following graph is presented:

Looks rather convincingly, doesn't it?

But there is an eerie similarity with the picture presented in 2008:

The last column is based on only 9 months, the full 12 month result would be USD 81M, while the company made a PAT of USD 88M in 2009.

The rather strange fact (which isn't mentioned at all in the 2014 report) is that POSH made a higher profit in 2008 and 2009 than each year after that, despite:

- Receiving a huge capital injection by Maybulk in December 2008;

- A rights issue in 2012;

- The retained earnings over all those years.

This was what KPMG wrote in 2008:

The results of 2008 were more or less known in December 2008, so let's compare those with the results of 2011 and 2012, the timeline that KPMG indicated in the above paragraph.

It turns out those profits were only USD 26M (2011) and USD 54M (2012), a whopping 68% and 33% lower than the profit in 2008, while KPMG forecasted "substantial growth over the next three to four years".

So much for the rather poor forecasting capabilities of KPMG. And they can't blame the global recession for that, the acquisition of POSH by Maybulk in 2008 was right smack in the middle of it.

For the benefit of the reader, the full earnings picture of POSH, all amounts in USD:

2006: 0M (company just started)

2007: 9M (first acquisitions, paid-up still very low)

2008: 81M (injection 160M from PCL, 221M from Maybulk)

2009: 88M

2010: 28M

2011: 26M

2012: 54M (rights issue of 150M)

2013: 73M

Is this indeed a "track record of strong financial performance", as is claimed in the 2014 prospectus by the Chairman? Based on the last three years results, may be. Based on the last six years not really, I think.

Return on Equity in the last three years was 4.6%, 9.0% and 11.1% despite being rather leveraged, not impressive.

There doesn't seem to be growth in revenue over the last three years. Most of the growth in profit comes from "Other operating income", not sure how recurring those are (below numbers have not yet been adjusted downwards):

Another interesting topic is the valuation by KPMG, this is the current one:

This is the valuation of 2008 based on adjusted NA:

And their valuation of 2008 based on DCF:

What is remarkable is that the valuations of 2008 and 2014 are almost identical, while:

- A large capital injection was made in 2008, 58% of which was from Maybulk;

- There was a rights issue in 2012 bringing in even more capital, USD 150M;

- POSH has accumulated earnings over 5.5 years between the valuation in 2008 and 2013, close to USD 300M;

- In 2008 there was a huge global recession going on, with all valuations very cheap, while in 2014 valuations appear to be on the high side;

The only way to explain the peculiar valuations is to assume that KPMG's valuation of POSH in 2008 was simply much too high, unrealistically so.

For one part (the DCF valuation), KPMG should fully take the blame.

For the Asset valuation, that was partly based on the valuation of Clarkson, about which I wrote under the title: "Clarkson, the valuer who didn’t believe his own valuation".

That title was indeed deemed to be correct (the authorities have confirmed that), the valuation of Clarkson was made on September 15, 2008 and was not valid on the day the prospectus was issued, November 25, 2008. In only a bit more than two months time values of vessels had collapsed, like almost all other asset values, making the valuation much too high.

The important question is: why did nobody question the valuation of Clarkson?

There are many maritime experts in the board of directors of Maybulk, POSH and PCL who should have known about the problems in this industry.

But even the non-maritime experts of those boards of directors, the writers of the prospectus AmInvestment Bank and the independent adviser KPMG, they should have guessed that the valuation might not be correct anymore, and should have actively sought clarification.

Why did no one contact Clarkson at the end of November or early December 2008? They were just one single phone call or email away.

A new, updated valuation by Clarkson would have had a huge impact on the adjusted net assets, the more since POSH was highly geared.

And that would have enabled the non-interested directors of Maybulk to renegotiate a much fairer deal for the shareholders of Maybulk.

Maybulk's shareholders deserved a much larger chunk of POSH in exchange for its large injection in POSH, in my opinion roughly 50% of the shares instead of the 21% it would receive. Profit contributions in the subsequent years would then have made a much higher impact, and at the coming IPO of POSH Maybulk would not need to buy additional shares to keep a minimum shareholding of 20%, it could even consider selling some shares, if the price is right.

Wednesday, 28 September 2011

Maybulk/POSH: KPMG's "independent" advice

The Net Assets of POSH as at September 30, 2008 were USD 188 million, which included a large amount of Goodwill (USD 295 million). The assets were bought during economic boom times. According to the offer POSH was worth USD 780 million, more than four times the Net Assets, and that during the fierce recession. Many listed companies with long track records were trading around Net Assets, some even below it, some even below the net cash, with single-digit PE’s (some as low as 5 or even lower) and with high dividend yields. It was up to KPMG to give an independent advice on this deal, during these global economic conditions.

The first method used by KPMG was the DCF (Discounted Cash Flow) approach. I have written about this in the past:

As usual, many pages were written about the approach, the key bases and assumptions, although the economic crisis is rather strangely left out of the picture. When KPMG revealed its results (POSH is worth between USD 613 million and USD 894 million), it left out the calculation itself. In other words, the readers couldn’t check anything and that while the whole circular contains 130 pages and the calculation could be presented in one single page. I assume that KPMG has used very high (unrealistic high) growth forecasts for POSH which resulted in the extreme valuation numbers. A hint of KPMG’s growth forecasts can be found here:

Did POSH indeed perform that well? In 2009 earnings did grow by 8% to USD 88 million, not bad given the economic conditions but disappointing given the huge cash injection from Maybulk. In 2010 profit declined substantially by 72% to USD 25 million, while in the first half of 2011 profit declined further to a paltry USD 3 million. It looks like KPMG had wildly overestimated Maybulk’s future profits.

The second method that KPMG used is the adjusted net assets in which assets were revalued as appraised by Clarkson.

- USD -107 million, Tangible net assets (vessels minus borrowings)

- USD 295 million, Add Goodwill

- USD 250 million, Add Revaluation existing vessels

- USD 440 million, Add Revaluation vessels under construction

For a grand total of about USD 880 million.

This calculation is, in my opinion, very flawed for the following reasons:

[1] The goodwill of USD 295 million is in respect of the acquisition by POSH of its subsidiaries. However, those subsidiaries were bought during the economic boom times, and it is debatable if this goodwill was still valid during the recession.

[2] KPMG adds the revaluation of existing vessels, however, there is a a huge overlap with the amount of goodwill since the vessels of POSH are the same vessels of its subsidiaries. In other words, one can either count goodwill on the subsidiaries or revaluation of the vessels in the subsidiaries, but you can’t have both.

[3] Revaluation of an asset is only allowed if the value can be measured reliably. During the worst global crisis of the last 50 years with all asset prices falling (including those of vessels) and the valuer of the vessels not supporting his own valuation anymore, we can safely assume that values can not be measured reliably. In other words, revaluation is simply not allowed.

“If fair value can be measured reliably, an entity may carry all items of property, plant and equipment of a class at a revalued amount, which is the fair value of the items at the date of the revaluation less any subsequent accumulated depreciation and accumulated impairment losses.”

[4] KPMG subsequently adds the revaluation surplus for the vessels under construction. First of all, the same problem applies as above; values can not be measured reliably, so this is not allowed. Secondly, a revaluation of assets under construction is not allowed under the Malaysian Accounting rules. And even if it was allowed, it would definitely not be General Accepted Accounting Practices (GAAP).

There are other ways to come up with valuations for POSH, ways that would have given a more rounded picture, but were (conspicuously) left out by KPMG:

One is to compare the valuation of POSH to listed companies in the same industry, companies that during Q4/2008 were trading at very low valuations: single-digit PE’s, high dividend yields, some trading at a discount to its Net Assets.

Another way is to compare the valuation of POSH to the value that other shareholders paid for its shares. Employees were allowed to buy 4.75 million shares of POSH at a price of USD 2 per share, at the same time when Maybulk was paying USD 6.50 for the same shares. The huge difference looks puzzling, to say the least.

And finally one could look at how much money PCL invested in POSH and how much money POSH had made, which would result in the Net Assets of about USD 188 million, or about USD 1.60 per share. Again, the difference with the USD 6.50 price that Maybulk would have to pay is very high.

Let’s assume for argument sake that both valuations done by KPMG were fair, both around USD 6.50 per share, the price Maybulk would pay. Would it then be a fair deal? Both valuations depended on all sorts of assumptions, but the price paid by Maybulk was supported (for 90%) by cold hard cash. Because of this unequal situation, Maybulk should have insisted on a huge margin of safety, probably at least 50%, given the amount of assumptions and the huge uncertainty in the global economy.

To put things further in perspective: Maybulk would bring in 53% of the assets of POSH (post deal), but only get 22% of the shares. That doesn’t seem right at all, Maybulk shareholders deserved a much better deal than this.

KPMG deemed the proposal to be “fair and reasonable” and recommended shareholders to vote in favor. Although they gave this very strong recommendation, yet they were scared of any consequences and therefore insisted that they hadn’t verified information provided to them:

And in another statement, they even denied any liability:

I think that is highly debatable, I think there is a very good case to be made that KPMG is liable. Anyhow, I strongly recommend the authorities to come down hard on independent advisers who issue these kinds of statements:

If advisers don’t want to take any responsibility while at the same time they make very clear judgment calls which have consequences for the voting behavior of shareholders then they should simply not be allowed to be independent adviser.

Another issue is the put option that Maybulk received: Maybulk has the option to sell the POSH shares back to PCL for 1.25 times the price it paid after 5 years (this option was balanced out by a Call option by PCL). KPMG compared the return (4.6%) to the 3.2% Maybulk received on its fixed deposit and calls it “acceptable”. But this is really comparing apples with oranges, during the crisis the fixed deposits were guaranteed by the Malaysian government (as announced on October 17, 2008), while PCL is a company. KPMG should therefore have compared the 4.6% return to the yield of AAA or AA corporate bonds, which were yielding between 10% and 15% per year. Also, there is the currency risk, Maybulks profit is calculated in RM while the investment is done in USD. This is a very real possibility, at this moment the USD has weakened against the RM, causing Maybulk to have booked paper losses. Another issue is that it is not sure if the Put option will be called, it is possible that the POSH investment will not work out at all, but that the Board of Directors of Maybulk decides not to call the option. This is not hypothetical, since in my opinion this whole POSH deal should never have been approved by the Board of Directors, but they still did.

And lastly, KPMG writes the following:

I find this dubious at best; just having a single director would give Maybulk influence? As we have seen before, the cash that Maybulk injected in POSH had left the company two weeks later, where was the influence of the Maybulk director? Maybulk would appoint Dato’ Capt. Ahmad Sufian @ Qurnain bin Abdul Rashid as Director for POSH. This director was appointed to the Board of Maybulk in 1996, more than 15 years ago, and therefore (according to the Guidelines of EPF) his independency could be impaired by the long term participation. EPF will vote against renewal of this director.

My conclusion: I find it is simply unbelievable that KPMG's advice letter in its current form was allowed to be included in the circular without any interference from the Board of Directors of Maybulk (which included several accountants) or from Bursa Malaysia (responsible for enforcement of circulars)

Friday, 23 September 2011

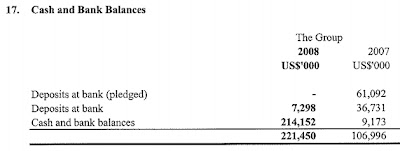

Maybulk/POSH: What happened to the Cash?

To recap: PCL, Majority Shareholder of Maybulk and POSH invited Maybulk to invest USD 221 million (about RM 800 million, 90% cash plus one vessel) for 22% of POSH, which had Shareholders Funds of only USD 188 million, which includes already goodwill of USD 295 million.This controversial deal happened November/December 2008, in the midst of the global recession.

The first question that any investor would ask if somebody would approach them to invest in their company would be: "Why, what is the purpose?". Unbelievable but true, in the Maybulk/POSH circular of 130 pages, this is not mentioned one time. The circular can be found here:

http://www.bursamalaysia.com/website/bm/listed_companies/company_announcements/circulars_to_sholders/index.jsp

There are (not surprisingly) many references in the rules that the purpose has to be mentioned, for instance in the Due Diligence:

On December 10, 2008, the EGM voted in favour of the acquisition, on December 16, 2010 already the whole transaction had been completed.

The Securities Commission and/or Bursa Malaysia can simply order the Directors to come to their office and ask them what the purpose was (I hope they have done this by now). Unfortunately, I only have the publicly available information to work with, so I acquired the 2008 year report of POSH.

I expected to see a large amount of cash in the accounts on December 31, 2008 since the money had been deposited only two weeks before. But to my surprise, almost all the money had magically disappeared!

What had happened to all the money? Looking further in the accounts, there was only one reasonable explanation:

All the money had been used to repay the loan to PCL!

I have checked the 2008 Year Report from PCL, and that does indicate the same, a large amount of cash:

POSH could have used the money for working capital, for repayments of its bank borrowings, for the acquisition of additional vessels or could even have bought over whole companies. This was in the midst of the worst global recession of the last 50 years, asset prices were falling out of the sky and there were lots of bargains everywhere. Using it solely to repay all the loans to PCL is about the worst purpose that could have happened to POSH and thus for Maybulk who had just invested in POSH.

Was this the purpose for Maybulks investment in POSH known to the Directors of Maybulk and to advisers AmInvestment Bank and KPMG? Was this the reason why the purpose of the investment was nowhere given in the circular, knowing that Minority Shareholders would not like it at all?

There are more indications for this theory. According to the Prospectus Guidelines, there should have been a recent, audited account of POSH, not more than six months old. But there wasn't, another breach of the rules. Because there was no recently audited account, only the full details were given of the accounts from 31-12-2007, almost one year old, and that for a very young and quickly changing company. There were some numbers given regarding the nine month period until September 30, 2008.

Total borrowings had ballooned to USD 412 million, a worrysome amount. But it only mentioned the interest-bearing debts of POSH, while the debts from PCL were non interest bearing. Why did it not mention these, this is essential information?

Below in green it mentions the Gearing Ratio, but it only uses again the interest bearing debts, while the definition of Gearing Ratio is very clearly regarding all debt, both interest and non-interest bearing. Many accountants must have been involved in this deal (Maybulk directors, AmInvestment Bank, KPMG), did they not spot this obvious fact?

As often in these kind of circulars, no alternative is mentioned what Maybulk otherwise could do with the money. One glaring alternative would be to just hand the money to its shareholders in the form of a bumper dividend. It didn't do that, however.

And what did PCL do with the money? It paid a huge dividend of USD 400 million to its shareholders. Money for a decent part from Minority Shareholders from Maybulk.

So far we have seen the following significant breaches of rules:

The first question that any investor would ask if somebody would approach them to invest in their company would be: "Why, what is the purpose?". Unbelievable but true, in the Maybulk/POSH circular of 130 pages, this is not mentioned one time. The circular can be found here:

http://www.bursamalaysia.com/website/bm/listed_companies/company_announcements/circulars_to_sholders/index.jsp

There are (not surprisingly) many references in the rules that the purpose has to be mentioned, for instance in the Due Diligence:

On December 10, 2008, the EGM voted in favour of the acquisition, on December 16, 2010 already the whole transaction had been completed.

The Securities Commission and/or Bursa Malaysia can simply order the Directors to come to their office and ask them what the purpose was (I hope they have done this by now). Unfortunately, I only have the publicly available information to work with, so I acquired the 2008 year report of POSH.

I expected to see a large amount of cash in the accounts on December 31, 2008 since the money had been deposited only two weeks before. But to my surprise, almost all the money had magically disappeared!

What had happened to all the money? Looking further in the accounts, there was only one reasonable explanation:

All the money had been used to repay the loan to PCL!

I have checked the 2008 Year Report from PCL, and that does indicate the same, a large amount of cash:

POSH could have used the money for working capital, for repayments of its bank borrowings, for the acquisition of additional vessels or could even have bought over whole companies. This was in the midst of the worst global recession of the last 50 years, asset prices were falling out of the sky and there were lots of bargains everywhere. Using it solely to repay all the loans to PCL is about the worst purpose that could have happened to POSH and thus for Maybulk who had just invested in POSH.

Was this the purpose for Maybulks investment in POSH known to the Directors of Maybulk and to advisers AmInvestment Bank and KPMG? Was this the reason why the purpose of the investment was nowhere given in the circular, knowing that Minority Shareholders would not like it at all?

There are more indications for this theory. According to the Prospectus Guidelines, there should have been a recent, audited account of POSH, not more than six months old. But there wasn't, another breach of the rules. Because there was no recently audited account, only the full details were given of the accounts from 31-12-2007, almost one year old, and that for a very young and quickly changing company. There were some numbers given regarding the nine month period until September 30, 2008.

Total borrowings had ballooned to USD 412 million, a worrysome amount. But it only mentioned the interest-bearing debts of POSH, while the debts from PCL were non interest bearing. Why did it not mention these, this is essential information?

Below in green it mentions the Gearing Ratio, but it only uses again the interest bearing debts, while the definition of Gearing Ratio is very clearly regarding all debt, both interest and non-interest bearing. Many accountants must have been involved in this deal (Maybulk directors, AmInvestment Bank, KPMG), did they not spot this obvious fact?

As often in these kind of circulars, no alternative is mentioned what Maybulk otherwise could do with the money. One glaring alternative would be to just hand the money to its shareholders in the form of a bumper dividend. It didn't do that, however.

And what did PCL do with the money? It paid a huge dividend of USD 400 million to its shareholders. Money for a decent part from Minority Shareholders from Maybulk.

So far we have seen the following significant breaches of rules:

- no mentioning of the purpose of Maybulks investment in POSH

- no recently audited accounts (less than 6 months old)

- incomplete financial picture leaving out (for instance) non-interest bearing debts

- incorrect calculation of the gearing ratio

- Clarkson, the valuer who didn't believe his own valuation

- the magical accounting tricks of KPMG

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)